Black History in La Plata County

Understanding African American history in the Southwest is crucial. It sheds light on the African American experience beyond the more commonly known history of the Civil Rights Movement in the American South. While the struggle for civil rights and racial equality was significant in the Southern states, African Americans in the Southwest experienced unique challenges and triumphs seldom recounted.

The African American history of the Southwest is intertwined with the larger narrative of the westward expansion of colonization on the American frontier. Learning this history helps us to recognize their crucial role in its development, from working as ranchers to building communities and businesses.

Exclusion of African American History

African American history has been deliberately suppressed in the dominant narratives of the United States. This erasure omits African Americans' contributions, achievements, and experiences. In the Southwest, many important events and figures in African American history have also been neglected or misrepresented in mainstream discussions of Western culture.

One of the main reasons that African American history in the United States was excluded is the pervasive idea of a "white Anglo-Saxon Protestant" (WASP) culture that has dominated American history and culture. This narrative has tended to overlook the experiences of people from other ethnic and racial groups, including Hispanics, African Americans, and Indigenous peoples. In the case of African Americans, their deliberate exclusion of African American individuals from academic institutions and historical research has played a role in the erasure of their histories.

Additionally, African Americans were prevented from holding positions of influence and authority, which made it challenging for their viewpoints and life experiences to be incorporated into popular historical accounts.

In most historical texts documenting the Southwest, African Americans were pushed to the margins of the pages and chapters that mentioned them. Only a few mentions in the literature note the Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Lewis, the “motley railroad crew” that built the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad (D&RG), or the predominantly Black red-light district in Durango. Notable individuals like George Motley, who arrived in Colorado with General William Jackson Palmer scouting a Denver & Rio Grande Railroad route, were depicted in most secondary sources as unnamed “excellent colored servant[s].”

However, African Americans have undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping the region's cultural, economic, and political landscape. Many stories exist of African American entrepreneurs and business leaders like Madame C.J. Walker, who built a successful beauty empire in Colorado.

Black cowboys also played a significant role in developing the region's ranching industry, with many African Americans working as ranch hands and cattle drivers.

Recognizing and learning from Southwestern African American history is essential to promoting a more accurate and inclusive understanding of Durango. It’s a rich collection of stories that might go as far back as the 1500s.

1500-1600s

Narváez Expedition

Following Columbus’ conquest in 1492, the Spanish Empire arrived in the Southwest 1530s after dispatching an expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who died in 1528. Estevanico, also known as Esteban de Dorantes or Mustafa Azemmouri (مصطفى الزموري), was with the Narváez expedition and was the first recorded African in North America. Estevanico made it to modern-day New Mexico in the 1530s.

The later colonial Spanish population that settled there did not venture very far north often due to fear of raids from Indigenous peoples. However, that does not eliminate the possibility of people of African ancestry from reaching Southwest Colorado in this period.

1700s

Rivera and Dominguez-Escalante Expeditions

There were further opportunities for African American activity during the 1700s. Following the Rivera expedition in 1761 and the Dominguez-Escalante expedition in 1776, there was trade and travel north of New Mexico. In the primary source literature likely held in New Mexico or the Mexican National Archives, there may be accounts of expeditions north, tax records of Genízaros living on the fringes of Colonial Spanish control, or trade records with Indigenous nations that detail African American individuals living in the Southwest during this time.

1800s

Beginning of Recorded African American History in the Southwest

The recorded history of African Americans in Colorado begins 1850s and is tied to the state's military and mining history, as well as to the larger trends of African American migration in the United States. In the 1860s, African Americans began migrating west with other groups as soldiers, cowboys, or homesteaders, though not remembered in the popular culture as having participated.

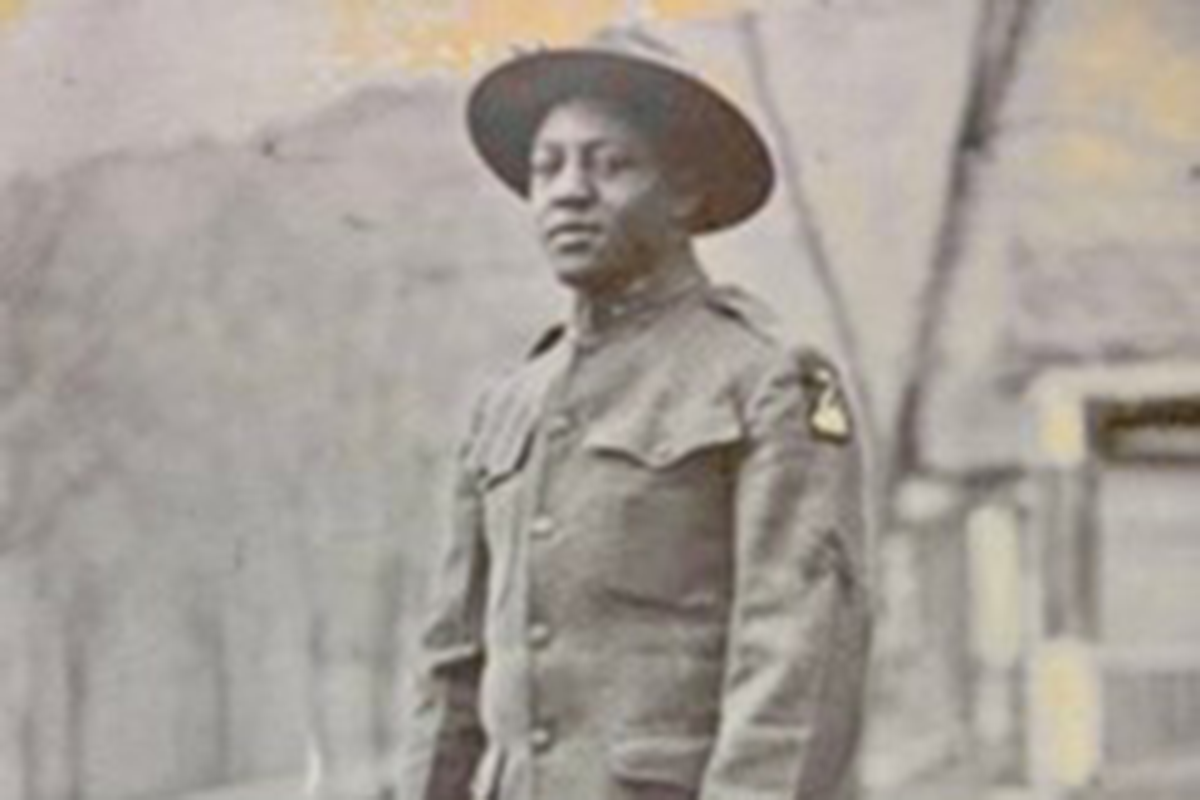

Buffalo Soldiers

In the 1860s, the United States military was involved in frequent conflict with Indigenous nations in the Southwest. In response, the U.S. sought to clear Indigenous people from the land entirely—much like the British. As a result, the late 19th century saw the arrival of many African American soldiers who were dispatched to the Southwest to further the Unites States' goal of colonization.

In 1866, African American troops nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers” arrived. They served under white officers in the 9th and 10th Cavalry and under four Infantry Regiments. These regiments had many soldiers who had fought for the Union in the Civil War under the United States Colored Troops and new soldiers who sought opportunity and equality through military service. The Buffalo Soldiers would be disbanded later in the early 1950s.

In 1882, the 9th Cavalry was encamped at Fort Lewis, a U.S. Army post that operated from 1878 to 1891. The presence of Fort Lewis and the need to feed and supply the soldiers there is credited with kick-starting the local agricultural economy, as it created a reachable market for surplus goods.

Meeker Incident

In 1879, Indian agent Nathan Meeker tried to convert the White River Utes at their reservation to follow the lifestyle of sedentary farmers and Christian beliefs. After a year of tension, Meeker plowed a favored green valley used for grazing and racing Ute’s horses, threatened to withhold annuity payments, and asked that the cavalry patrol the woods to prevent the Ute people from hunting or foraging for their food. In response, Meeker was attacked and wired the military for aid.

Company D of the 9th Calvary rushed to the aid of the U.S. Army trapped under fire from the defending Ute people. The Utes took the approaching troops as a sign of war, killed Meeker and 10 of his men, and took hostages. Ute snipers quickly pinned down the troops Meeker had called.

Company D had been surveying the Colorado-Utah border and was the closest possible relief for the pinned-down soldiers. Henry Johnson, an African American soldier, received the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Battle of Milk River. Johnson’s recognition begins a recurring theme in Unites States history: African American earning recognition through acts of military service and those actions being tied to the Unites States’ ethnic of Indigenous nations.

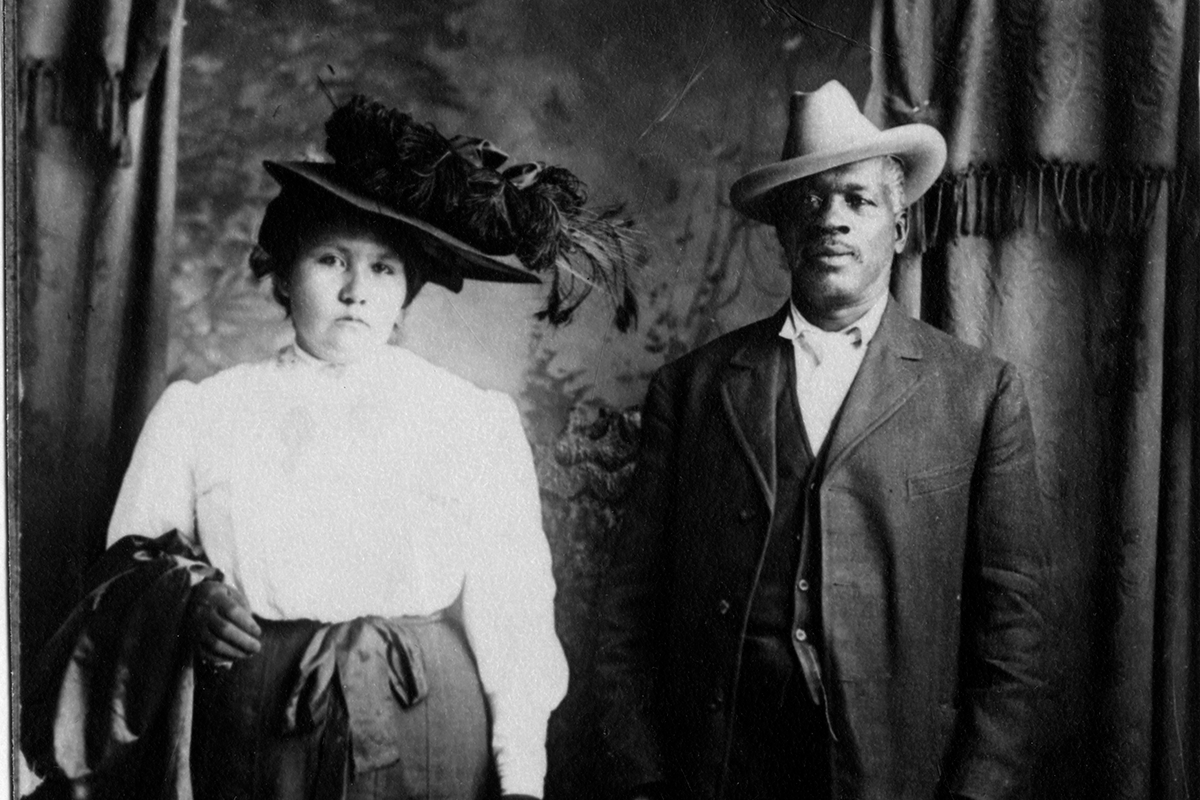

John Taylor

African Americans have been part of Southwest Colorado’s history since at least 1870, when John Taylor settled in the Pine River Valley. It might be earlier with undocumented figures that might have traveled through as explorers or soldiers.

John Taylor, an African American soldier, was born in 1841 in Kentucky to enslaved parents and died in 1935 in Ignacio, Colorado. Taylor had fought for the Union during the Civil War and later joined the Buffalo Soldiers. He joined a group of Chiricahua Apache in 1870. Eventually, he returned to the Four Corners region as a skilled interpreter fluent in Apache, Spanish, Hopi, Navajo, and Ute.

He married Kitty Cloud, a citizen of the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, and they had four children that survived into adulthood, including later tribal council member Euterpe Taylor. He worked as a Bureau of Indian Affairs interpreter for Ute affairs from 1896 to 1935. He died on the Southern Ute Reservation at 93.

Taylor’s descendants would face a world shaped by Jim Crow and the “one drop rule” that saw no nuance to their ancestry. For them, the culture of racial prejudice extended far beyond the days of the frontier.

Frank Fitchue

Frank Fitchue was celebrated for stopping a bank robbery in 1883 at First National Bank in Durango while employed as a janitor. Fitchue arrived in Durango in the 1880s, drawn by railroad construction work. He would work at the Strater Hotel as a porter and later owned a copper mine in Rico called the Missouri Girl and agricultural lands in Bayfield.

Fitchue died in 1917 and was only honored by the bank in 2007. Fitchue’s story of coming to La Plata County follows a familiar pattern, with the railroad, travel, and hospitality industries providing jobs for African Americans that went West.

Colorado’s Policy towards African Americans

A series of civil rights laws passed in Colorado suggested that on paper, at least the territory and later the state were a welcoming home for African Americans. The 1867 Territorial Suffrage Act allowed Black men to vote years before the Fifteenth Amendment. The Colorado Constitution of 1876 prohibited racial discrimination in schools. The 1896 Civil Rights Act of Colorado provided “that all persons be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of all places of public accommodation, such as restaurants, barbershops, theaters, and transport conveyances.” Unfortunately, enforcement of these laws was not reliable or dependable.

Early Durango and the Arrival of African American Workers

In 1878, a group of prospectors led by William Jackson Palmer discovered silver and gold in the Southwest region. The discovery led to a rush of people seeking their fortunes in the region, and the town of Durango was established in 1880. Durango was later incorporated into the D&RG branch lines that were constructed in 1887.

Durango’s economy was dependent on Silverton’s silver and other mines. Businesses in Durango smelted the ore and shipped out commodity products. Ample supplies of timber, coal, and clay in the region aided the growth of the small industrial town, with railroad spur lines bringing those commodities within easy reach.

The first recorded African American residents of Durango were William and Lucinda Hood, who arrived in 1880. Many other African Americans, including railroad workers and homesteaders, followed them.

Construction of D&RG and Formation of Black neighborhoods

African American newspapers in the East carried news articles about the construction efforts of the D&RG in 1880 as well as advertisements placed by the D&RG and others that represented La Plata County as an ideal place to work and settle. The advertisements did not, however, frame the region as a special destination for African Americans. The expansion of the railroads offered work not only in construction but as porters, cooks, janitors, waitstaff, and similar service positions in hotels, restaurants, and other businesses connected to travel. According to Black settlers’ later accounts, this ad copy vastly oversold the land's ease of working.

The red-light districts housed much of the working class, non-Anglo population, located approximately where Durango Town Plaza is today. Across the Animas River, near Schneider Skate Park today, was Webb Town. Near Smelter Mountain was the neighborhood of Santa Rita. These neighborhoods were likely formed from informal segregation pressures rather than codified laws. The 1893 Silver Panic, a crippling blow to Durango’s mining industry, would further worsen relations between the Anglo and non-white residents of Durango.

It is hard to get a clear quantitative picture of the Black population in Durango before more rigorous eras of the decennial census. However, the years between 1880-1924 appear to be when most of La Plata County’s initial African American population arrived.

The State and Federal census of 1885 showed Durangoans were mostly native-born, white, and married, with two-thirds of the white population from Great Britain and Ireland and one-third from Germany. African Americans were a small fraction of the town’s population.

The arrival of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad brought laborers via its initial construction and the travel, hotel, and associated service jobs that came with it; this period of 1880-1924 appears to be when most of La Plata County’s initial African American population arrived. The African American community that settled in La Plata County came ahead of the Great Migration (1910-1960), which transferred over half of the African American population out of the South.

1900s

The Early 1900s

The African American community members in Durango would continue to thrive despite de facto segregation, racist editorials, and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Southwest Colorado in the early 1900s. While African Americans in Durango faced this discrimination and segregation, they also demonstrated resilience and perseverance in facing these challenges. The community continued to grow and contribute to the city's history and development.

Life for African Americans in the Early 1900s Durango

African Americans in Durango formed their close-knit community, which provided them with support and solidarity. They established churches, such as the African Methodist Church, built sometime after 1900 as a hub for the community's social and religious activities. The African Methodist Church was often a significant organizing force in African American communities in the early twentieth century.

Oral history interviews from Santa Rita residents confirm that all children had access to Durango schools via the public school system and at Sacred Heart Church. Later records show schools established exclusively for African American children under a New Deal program.

The job market for African Americans was somewhat restricted to the travel, hotel, and service jobs that came with D&RG, though there were Black cowboys that drove cattle across the landscape. Employment opportunities as porters for the D&RG or service positions at the local hotels were frequently mentioned in Black newspapers in Denver.

An article from the Weekly Ignacio Chieftain in the autumn of 1919 shows how the larger La Plata County community treated Durango’s growing African American community, celebrating George Barnett, Charles Trotter, and Ben Owens’ hunting party bringing back a “five-point, 360-pound dressed buck.” Local Black households were listed as entering competitions in the La Plata County fair.

Durango’s Black community was frequently mentioned by the Denver African American newspaper The Statesman (later The Denver Star) up through the 1920s. Prominent Black households like the Barnetts, the Wrights, and figures like Frank Fitchue were written about with pride in Denver. Parties, weddings, and other celebratory news items pertaining to Durango’s African American community were also celebrated.

The Ku Klux Klan in Durango

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan takeover over the state and local government in Colorado, including Durango and Bayfield. Colorado had the second-highest per capita Klan membership in this era. Governor Clarence Morley, members of the state supreme court, Denver’s mayor, police chief, and others in the justice system were all Klan members in this peak of activity.

In Durango and Bayfield, there were Klan marches, cross burnings, and a string of arson. The KKK even threatened to burn down the convent and Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

During the Klan years in Colorado, the local KKK had their newspaper called The Durango Klansman. Reviewing the literature that discussed this era of the Klan, authors tend to focus on the organization's anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, and anti-Hispanic emphasis; this is not incorrect, but it may obscure that the anti-Black rhetoric was still very present and likely active. A Durango Klansman article from 1925 makes this plain: “Now, as in the days of old, the dissolute negro is a bitter enemy of the Ku Klu Klan.”

The very first page opens with a declaration of a creed that frames white supremacy as divinely ordained.

The Denver Klan membership ledgers contain three names listing Durango as their home. There may be many more that gave other places of residence or used pseudonyms. It is also likely that La Plata County members of the KKK never bothered going to Denver to officially sign the ledger.

At Christmas, the Durango Klan burned a large cross on Smelter Mountain overlooking the city in 1925. African American residents took little comfort in the Klan’s rebranding as primarily anti-Catholic. Nor was that the only cross burning on record. In addition, masked riders interrupted cemetery services, and local shopkeepers were also intimidated.

The Fort Lewis Collegian in the 1930s reveals the KKK’s normalization of prejudice and ignorance affecting the nation did not spare the higher education institution. Articles about parties and dances mention minstrel performances and blackface costumes. An educational event on Southern life and culture featured a faculty member “disguised as a negro”.

Bayfield KKK records show the long-term persistence of the Klan in the town, with businesses adopting names to display affiliation and indicate hand signs or signals to do the same in person. The last public Bayfield and Ignacio Klan meetings were in 1927 and 1928. The Klan remained active and visible long after the peak of their power in 1925, with records from other parts of Colorado like Colorado Springs reporting on cross burnings through the 1930s.

Exodus from Durango

The peak of the Klan years in Colorado in 1925, the impact of the Great Depression, and the shift to a wartime economy in World War II were a confluence of events and long-term trends that appears to have made La Plata County as a less desirable place for non-Anglo peoples to settle in or remain.

It was not a singular cause that drove African Americans out, but greater economic opportunities and lower costs of living elsewhere certainly played a part. People who saw military service were exposed to other possibilities, and by the end of World War II, returning soldiers found Colorado segregated in a similar manner to the South. The 1920s saw the state courts uphold racially restrictive housing covenants, and interracial marriage bans were upheld in 1942.

Government policies subsidizing and incentivizing white homeownership while excluding others likely contributed to African Americans leaving Durango as they did elsewhere. The Home Owner’s Loan Corporation established mortgage lending grades that stigmatized “undesirable populations.” Similarly, veterans benefits, the G.I. Bill after WWII, USDA loans and assistance, and other government programs were not available in the same manner to non-White populations.

The economic, housing, and social barriers made it difficult for African Americans to thrive in Durango during the mid-20th century. As a result, many chose to leave the area for better opportunities and more welcoming communities. This left Durango with only a fraction of its small African American population.

African Americans in Durango Today

Today, Durango, Colorado has a population of approximately 18,000 people. While African Americans comprise a relatively small percentage of the city's population, there is a small but active African American community here.

According to the United States Census Bureau, as of 2020, African Americans make up less than 1% of the total population of Durango. Despite their small numbers, African Americans in Durango have formed a tight-knit community that has actively promoted diversity and inclusion in the city.

One of the most prominent organizations in Durango's African American community is the Black Student Union (BSU) at Fort Lewis College. The BSU is a student-led organization that focuses on community building, promoting awareness and education about African American culture and history, and addressing racial inequality and social justice issues.

Additionally, there have been many African-American-owned businesses in Durango, including restaurants and retail stores. These businesses contribute to the city's economy and add to its economic diversity.

While the Durango African community faces some of the same challenges for African Americans across the country, such as systemic racism and economic inequality, the community has shown resilience and strength. Through their activism, cultural contributions, and entrepreneurial spirit, African Americans in Durango have positively impacted the city and continue to play an essential role in its social and economic fabric.