Hispanic/Latinx History in La Plata County

Hispanic Americans have significantly contributed to the Southwest's economy, culture, and society. From the development of ranching and agriculture to the preservation of traditional arts, Hispanic Americans have played an essential role in shaping the region's identity.

The presence of Hispanic peoples in the Southwest dates back to the 16th century when Spanish explorers and colonizers arrived in Mexico and the southwestern United States. Understanding the history of Hispanic Americans in the region is crucial for understanding the historical roots of the Southwest's cultural diversity.

Exclusion of Hispanic History

The exclusion of Hispanic history in the United States is a complex issue with deep historical roots. Despite this long history, the contributions and experiences of Hispanics have often been overlooked or marginalized in mainstream narratives of American history.

One of the main reasons that Hispanic history has been excluded in the United States is the pervasive idea of a "white Anglo-Saxon Protestant" culture, which has dominated American history and culture. This narrative has tended to overlook the experiences of people from other ethnic and racial groups, including Hispanics, African Americans, and Indigenous peoples. In the case of Hispanics, this exclusion has been compounded by the fact that many Hispanics are of mixed racial and ethnic heritage, making it difficult to categorize them neatly within traditional racial and ethnic categories.

"Hispanic" is also complex because it is a broad umbrella term for people from various countries and cultural backgrounds. The U.S. government first introduced the term in the 1970s to describe people with roots in Spanish-speaking countries and regions, including Mexico, Spain, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. However, many people who fall under this label do not identify with it, as it ignores the diversity and nuances of their cultures and identities. Furthermore, "Hispanic" is often used interchangeably with "Latino," but these terms are not synonymous. While "Hispanic" refers to people from Spanish-speaking countries, "Latino" includes people from Latin America, including Brazil, which do not speak Spanish.

Another factor contributing to the exclusion of Hispanic history is the relative need for more political and economic power wielded by Hispanics in the United States. Despite being one of the largest and fastest-growing ethnic groups in the country, Hispanics are often underrepresented in political and cultural institutions, which can limit their ability to shape public perceptions of their history and culture.

In recent years, there have been efforts to recognize and celebrate Hispanic history in the United States. For example, National Hispanic Heritage Month is celebrated every year from September 15th to October 15th to acknowledge the contributions and achievements of Hispanic Americans throughout history. Additionally, there have been efforts to incorporate more diverse perspectives into American history curricula, which could help to combat the exclusion of Hispanic history in the United States—which goes as far back as the 1500s if we accept “Hispanic” as a linguistic identifier and not an ethnic one.

1500-1600s

Narváez Expedition and Colonization of the Southwest

Following Columbus’ conquest in 1492, the Spanish Empire arrived in the Southwest 1530s, after dispatching an expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who died in 1528. The Narváez expedition made it to modern-day New Mexico in the 1530s, preceding the Spanish settlement of modern-day New Mexico.

In 1598, Juan de Oñate led a group of Spanish settlers into what is now New Mexico, which included parts of present-day Colorado. Oñate claimed the land for Spain and established the first Spanish colony in the region: San Juan de los Caballeros. One of the most important settlements established during this period was the town of Santa Fe, which was founded in 1610 and served as the province's capital.

The Spanish presence in the region brought with it significant changes, both for the Indigenous peoples and the natural environment. The Spanish introduced new plants and animals, as well as European diseases, which devastated the Indigenous nations.

The Spanish also brought their religion and culture to the region. They established missions and converted many of the Indigenous people to Christianity. The Spanish also brought with them the tradition of encomienda, a system of forced labor that exploited the Indigenous nations.

Throughout the 1600s, the Spanish continued expanding their control over the region, establishing new settlements and converting more Indigenous people to Christianity. However, the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 saw the Indigenous populations rebel against Spanish rule, expelling the Spanish from the region for over a decade.

1700s

Hispanic Presence in the 1700s

During the 1700s, Spanish colonists continued to move into the San Luis Valley, an area in Southwestern Colorado home to several Indigenous tribes, including the Ute, Apache, and Comanche. These colonists established several towns and settlements in the region, including San Luis, the oldest continuously occupied Colorado town founded in 1851.

Significant conflicts subsisted between the Spanish colonists and nearby Indigenous nations. The Ute and other tribes resented the encroachment of the Spanish on their lands and the imposition of Spanish customs and religion.

Despite these conflicts, Hispanic cultures in Southwestern Colorado continued to grow throughout the 1700s. The region became an important center of trade and commerce and a hub of cultural exchange between the Spanish and the Indigenous tribes.

Partnership with the Timpanogos

With aid from Indigenous guides, the Spanish explored north into southwestern Colorado. Juan Antonio Maria de Rivera traveled from Santa Fe to Gunnison in 1765. Later, Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante set out in 1776 to find an overland route from Santa Fe to Monterey, California. Their guides were Timpanogos, a close relation to the Ute and Shoshone peoples, and their route became the basis for the Spanish Trail.

1800s

End of the Mexican-American War

The early 1800s saw a major shift in the power structures in the region as the United States steadily gained supremacy in the region. In the 1820s, Mexico secured its independence from Spain. After gaining independence from Spain, Mexico was in a brutal conflict with the United States.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. As a result of the war, Mexico turned over control of the New Mexico and Colorado Territories to the United States, bringing soldiers, settlers, and railroads further west. Under the treaty, Mexican citizens were guaranteed a transfer of citizenship to the United States, and their property rights were supposed to be retained and protected.

In practice though, many of these new American citizens found their lives and livelihoods discriminated against by incoming waves of Anglo settlers that had little respect for rights, treaties, or land grants dating back to the Spanish era. New territorial governments published laws and conducted business exclusively in English, with no accommodations given to Hispanic delegates or communities.

Migration to Colorado from New Mexico

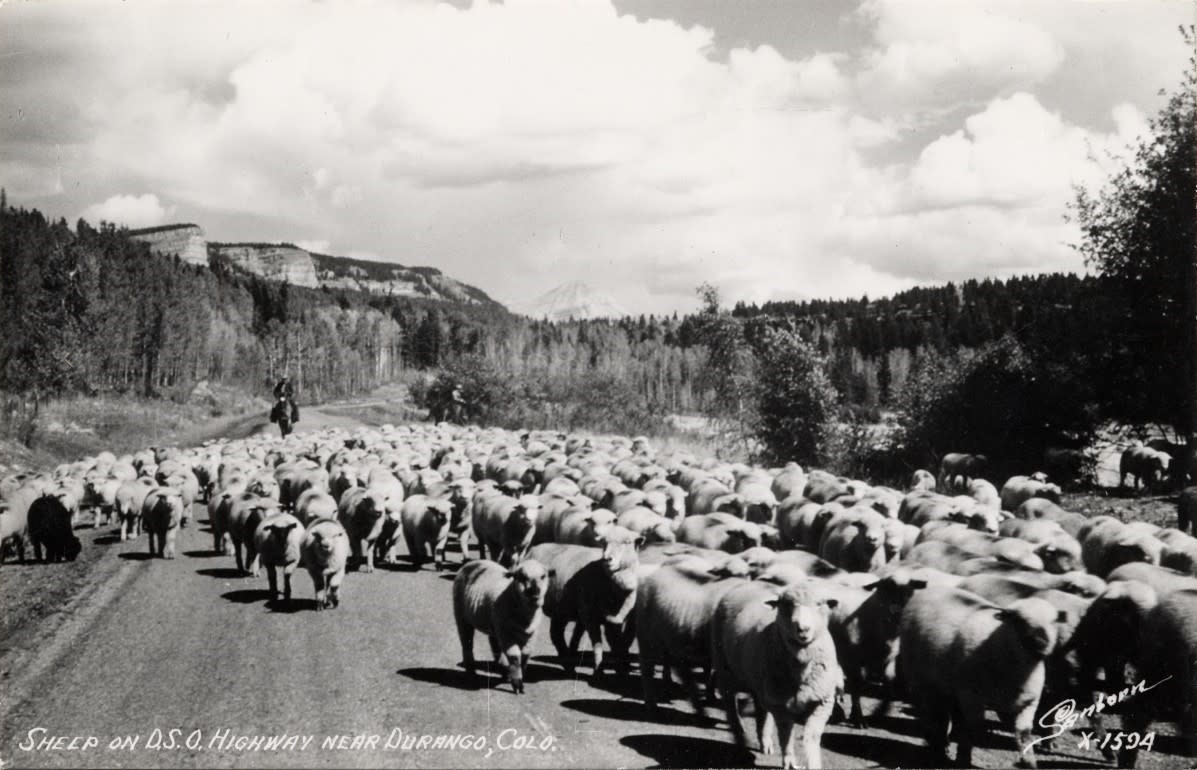

Mexican Americans in New Mexico, Texas, Arizona, and California, then displaced by the influx of settlers, saw an opportunity in Southwest Colorado. They were drawn by many of the same factors attracting migration in general: railroads, rapid industrialization, and agricultural work. Sheepherders under the partido system working for patrons in New Mexico were likely already present in southwestern Colorado.

Sheepherding in Colorado

In the 1800s, a long-running conflict formed between cattlemen and sheepherders over competition for rangeland. This dispute often had a racialized component, with more Hispanic, Greek, Basque, and Indigenous people raising sheep. Herdsmen from this era left marks carved into Aspen trees called arborglyphs to signify their presence.

In 1870, Colorado had 120,928 sheep, but a mere decade later, the state’s sheep census had grown to 946,443 animals. These sheep grazed more intensely than cattle, and the lands that had been traditionally grazed quickly fell into the hands of railroad companies, land barons, as well as states and the federal government—leading to ecological impacts that would last for generations. Numerous accounts of violence were perpetuated upon sheepherders.

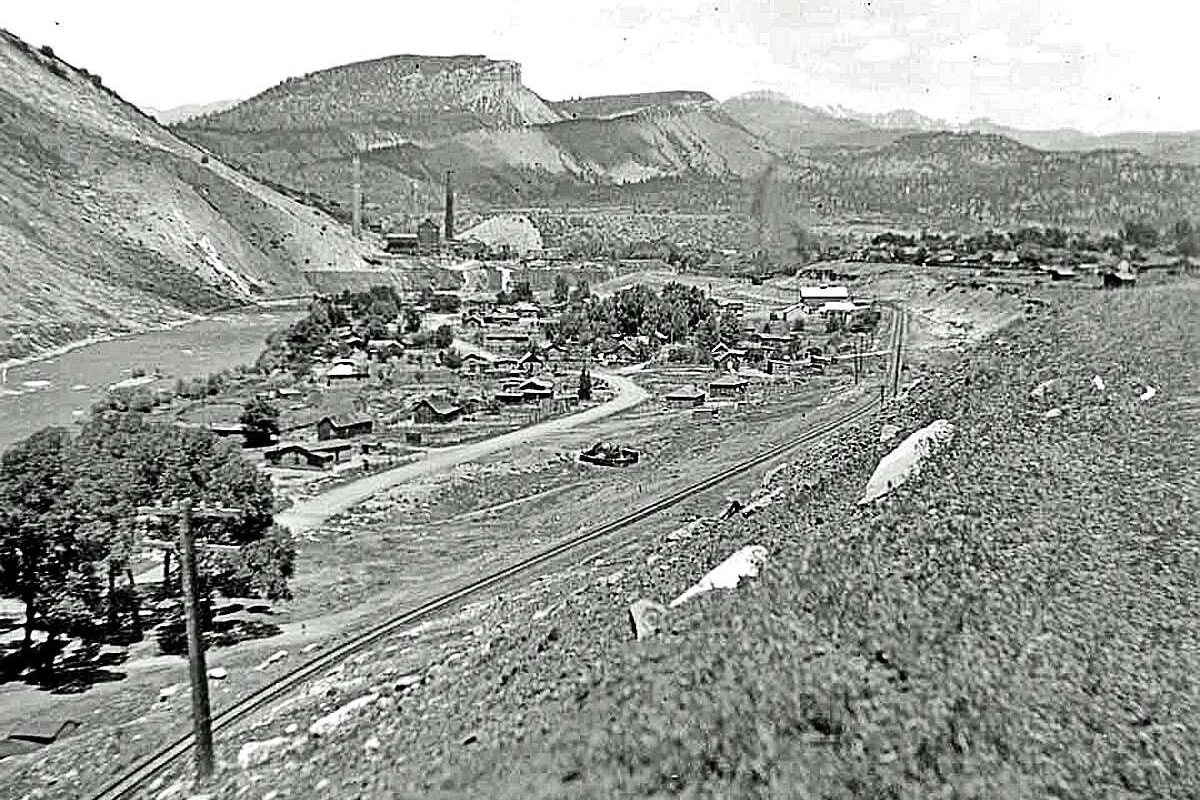

Animas City, established in 1876, and other early La Plata County settlements in the 1870s through 1880 were economically dependent on agriculture and ranching, selling surplus production within the region to Silverton and other mining camps and later the Fort Lewis military outpost established in 1878.

Early Durango and its Mining Economy

In 1878, a group of prospectors led by William Jackson Palmer discovered silver and gold in the Southwest region. The discovery led to a rush of people seeking their fortunes in the region, and the town of Durango was established in 1880. Durango was later incorporated into the D&RG branch lines that were constructed in 1887.

Durango’s economy was dependent on Silverton’s silver and other mines. Businesses in Durango smelted the ore and shipped out commodity products. Ample supplies of timber, coal, and clay in the region aided the growth of the small industrial town, with railroad spur lines bringing those commodities within easy reach. This era was marked by railroads, rapid industrialization, and agricultural work, attracting many Hispanic workers.

However, the 1893 silver panic struck a crippling blow to Durango’s growing economy. Mines, smelters, and rails remained, but the town’s economy moved to agricultural production.

Formation of Hispanic Communities and Neighborhoods

In 1898, the village of Castelar or La Posta, south of town, was founded from land given to Maria Antonia Head Tucson Vasquez from the Southern Ute Tribe. Hispanic and Indigenous peoples lived there in an integrated community. This would be the beginning of similar patterns of mixed families noted in Santa Rita and other neighborhoods.

The State and Federal census of 1885 showed Durangoans were native-born primarily, white, and married, with two-thirds of the white population from Great Britain and Ireland and one-third from Germany. Hispanic people formed a sizable portion of the town’s population.

1900s

The Early 1900s

In the early 1900s, Southwestern Colorado was home to an increasingly large Hispanic population composed of Mexican and Spanish immigrants and their descendants. Despite facing discrimination and marginalization, these communities played an essential role in the region's economic, social, and cultural development.

Historically Hispanic Neighborhoods in the 1900s

Durango historically had several Hispanic neighborhoods. Santa Rita, considered distinct from Durango then, was in present-day Santa Rita Park. The neighborhood was called initially Mexican Flats, then El Parral, and finally renamed Santa Rita in the early 1960s in honor of Santa Rita Betram, a deceased neighborhood girl. Proximity to the smelter and railroad operations increased the exposure of residents to environmental pollution, which would be classified today as an example of environmental racism.

The land above Santa Rita went by “la Mesa or Mesaro” and had better quality housing. There was also Webb Town, near the present-day DoubleTree Hotel, with homes in a depression near the bridge. Following Roosa Avenue north was la Chihuahua near the present-day Schneider Skate Park and la Plante just across the swinging bridge and south of the powerplant. These neighborhoods were also home to Southern European and Eastern European immigrants; however, those families tended to move out faster as they faced less discrimination.

There was some overlap with Durango’s red-light districts. If the local newspapers mentioned “Mexican Flats” it was usually in the context of violent crime or calamity, with editorial commentary that stoked prejudice towards residents. While existing sources can overstress the separation between Durango and Santa Rita, and while true in terms of being denied service in local businesses and welcome in general, Santa Ritans had lives and livelihoods integrated into the wider community.

Another example of environmental racism was the de facto exclusion of Hispanic people from livable tracts of land. These communities were pushed into low-lying flood-prone areas on the western side of the railroad tracks. During the 1911 flood homes in Santa Rita “found themselves islands.” 1909 flood waters put the entirety of Webb Town underwater and caused some families in Santa Rita to move.

Life for Hispanic People in Early 1900s Durango

Many Hispanic people in Durango formed tight-knit communities and worked to support each other. They established their businesses, schools, and churches, which served as important centers of social and cultural life.

Oral history interviews from Santa Rita residents confirm that children had access to Durango schools, both via the public school system and attending Sacred Heart Church.

Hispanic residents were reported working primarily at the smelter, in local restaurants and businesses, and the hotel trade. Many Hispanic residents also worked in agriculture, mining, and railroad jobs, often low-paying and dangerous. They likely pursued many different occupations than just what the census data recorded. Durango residents of all kinds have historically pursued all sorts of opportunities.

While there was no segregation from a legal standpoint, spaces for fraternization were implicitly separated along racial lines. There were clearly delineated saloons, bars, restaurants, and dance halls that separated the Hispanic population from the Anglo residents.

The Ku Klux Klan in Durango

In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan takeover over state and local governments in Colorado, including Durango and Bayfield. Colorado had the second-highest per capita Klan membership in this era. Governor Clarence Morley, members of the state supreme court, Denver’s mayor, police chief, and others in the justice system were all Klan members in this peak of activity. In Durango and Bayfield there were Klan marches, cross burnings, and a string of arson. The KKK even threatened to burn down the convent and Sacred Heart Catholic Church.

In this era, the Klan routinely espoused anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant, and anti-Hispanic rhetoric. However, this focus did not preclude the targeting of other people in the area, nor would it prevent people from being justifiably afraid of the possibility of violence and terror campaigns. In Durango and Bayfield alone, there were Klan marches, cross burnings, and strings of arson.

At Christmas, the Durango Klan burned a large cross on top of Smelter Mountain overlooking the city in 1925. Nor was that the only cross burning on record. In addition, masked riders interrupted cemetery services, and local shopkeepers were also intimidated.

Bayfield KKK records show the long-term persistence of the Klan in the town, with businesses adopting names to display affiliation and indicate hand signs or signals to do the same in person. The last public Bayfield and Ignacio Klan meetings were in 1927 and 1928. The Klan remained active and visible long after the peak of their power in 1925, with records from other parts of Colorado like Colorado Springs reporting on cross burnings through the 1930s.

The Denver Klan membership ledgers contain three names listing Durango as their home. There may be many more that gave other places of residence or used pseudonyms. It is also likely that La Plata County members of the KKK never bothered going to Denver to sign the ledger officially. These events, among others, would lead to a migration of non-white people from the area.

The Great Depression and the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934

The Great Depression was also tough on Hispanic people in Durango and was likely a compounding factor in their emigration away from the area. However, this was ameliorated when some jobs became available when the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) funded regional projects.

At the same time, the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 attempted to quell the competition and violence over grazing public lands through regulation, but this did not change the hearts and minds of local political leaders. Colorado Governor Edward Johnson used the State Patrol to close the border with New Mexico from Trinidad to Cortez, turning away all Hispanos. At least until their labor was desired and the border later reopened.

Mining Revived in Durango

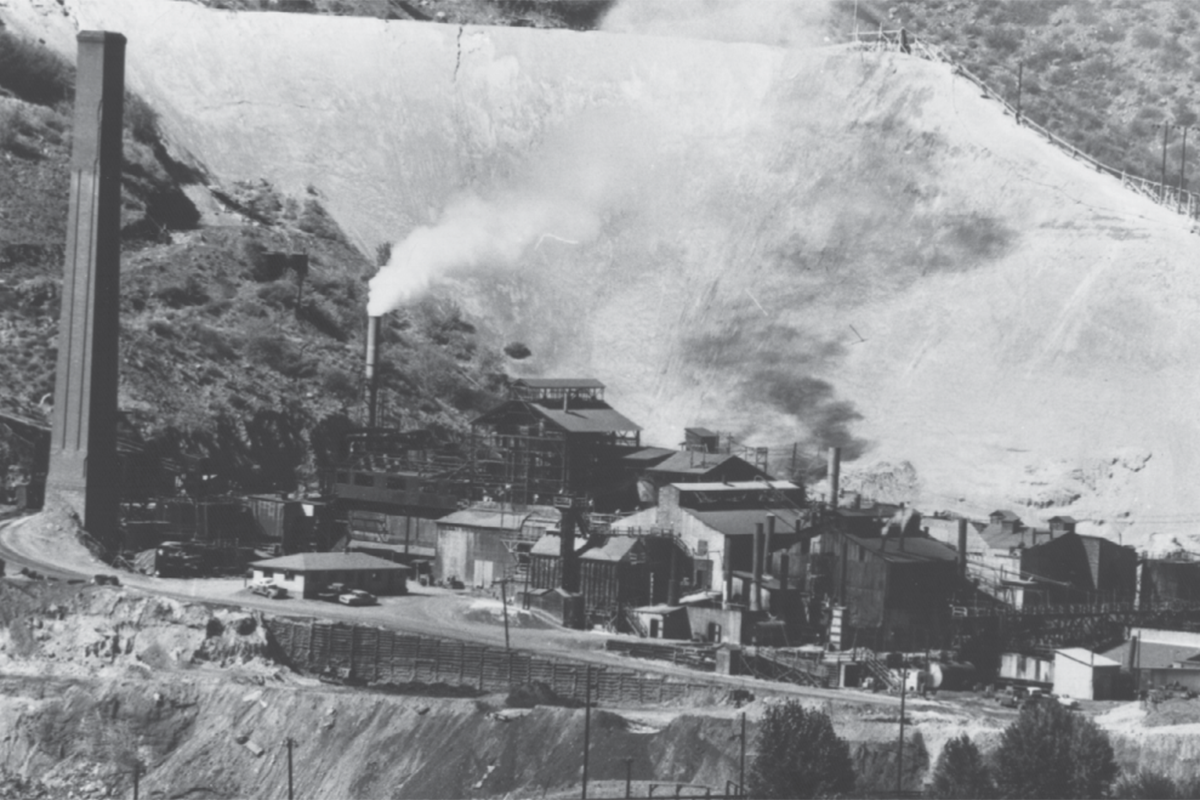

In the 1940s, wartime economies periodically revived the extraction and refining businesses. In WWII, the early Cold War, Uranium and vanadium mills significantly inflated Durango’s economy. Mill workers in Durango were not informed of the danger, though, nor were nearby residents. Many Santa Rita residents who worked for the mill directly interacted with the radioactive tailings.

The Vanadium Corporation of America (VCA) leased the Smelter Mountain uranium mill in 1948 and purchased it outright in 1953. Until 1963, the mill was an important source of jobs, including residents of Santa Rita who lived very close to the operation and the tailings pile. The Four Corners region has deposits of the mineral carnotite, an ore containing large amounts of uranium and vanadium.

Sourced within the Colorado Plateau, the VCA milled the ore on the side of Smelter Mountain on the banks of the Animas River, leaving behind a massive tailings pile estimated to be as large as 1.2 million cubic yards. Because of the secrecy inherent in the United States nuclear weapons program, the health risks of these tailings were not disclosed to the public or the workers involved. The choices government officials made did little to minimize the longer-term risks of exposure.

By 1978, Durango was considered the fourth-most uranium-contaminated site in the country, leading to massive clean-up efforts in the 1980s, with over a hundred new sites discovered in 2019.

Santa Rita Neighborhood and Fort Lewis College Students

After Fort Lewis College moved to its present-day location in 1956, students had made it a tradition to steal commodes from outhouses in Santa Rita and bring them back as trophies to be burned in the homecoming bonfire. In 1960, a group of students attempting to steal their fourth toilet was held at gunpoint by justifiably angry Santa Ritans. However, when Sheriff Herb McKinsey got involved the Fort Lewis students were not charged. This practice of tormenting neighboring locals may date back to the Hesperus campus.

By 1963, more cordial traditions were being formed between FLC and Santa Rita, like the Christmas party for the children of Santa Rita hosted by the FLC Drill Team and the Letterman’s Club. Students collected toys for donation and put on entertainment for the kids. This tradition extended into the 1970s and may have helped spur the creation of tutoring services offered by FLC students and professors to the children of Santa Rita. By 1966, the tutoring program was formalized as the La Casa de Amigos under Phyllis Mathewson.

Highway Development Cuts through Santa Rita

In the 1960s, landowners in Santa Rita were informed of the coming expansion of Highway 550 which was planned to eliminate the neighborhood. This followed other mid-twentieth-century trends for “slum removal” and “urban redevelopment” that used highway projects to eliminate poor neighborhoods.

Santa Rita residents were not reliably informed about when and where the highway would arrive. As early as 1963, La Plata County knew the approximate route would run through the neighborhood, but through the summer of 1966, residents were not kept in the loop from landowners and the local government.

There were many attempts to renovate the properties in Santa Rita to convince the local government not to build its expansion of Highway 550. Santa Rita residents also met with Durango realtors, many of whom told the residents there was not enough stock to absorb the neighborhood. This was exacerbated by the fact that Santa Rita fell outside the city limits, which prevented residents from voting in city council elections. This left the community adrift in the local political landscape looking largely to La Plata County officials.

By the 1970s, many Santa Rita residents had left, moving to other parts of Durango or leaving the community. A spate of fires appeared to signal the final days of Santa Rita as a place people lived; it’s unclear if these were accidental, arson, or some mix of both. It does not appear that the community had running water; many oral histories recount using a pump spigot well to get water, so the fires would have been much more difficult to combat.

James Casey of the La Plata County highway department finally confirmed the highway plans to residents in October 1966. However, the timeframe the state would compel them to leave needed to be clarified. Local landowner Curtis Johnson claimed the highway would arrive in June of 1968. James Casey claimed it would begin in April 1970 and start at the neighborhood's north end by the railroad tracks, with a six-month lead time for people to settle their affairs and move out. Unfortunately, the new highway did not finish until 1979, leaving residents distrustful. The Santa Rita neighborhood was later absorbed into the City of Durango’s municipal boundaries.

The dilemma faced by Santa Rita’s residents exemplifies La Plata County’s history of periodic housing shortages exacerbating de facto segregation.

Because of Santa Rita’s closing, mobile homes in neighboring communities were the only present and non-theoretical option for low-cost housing near Durango. Ignacio, Bayfield, Cortez, Aztec, and Farmington were popular destinations for families priced out of Durango at the time.

Today, a historical marker in Santa Rita Park informs tourists and residents of the community that used to be present there. But the dissolution of the neighborhood was not the end of the community and culture fostered there.

Hispanic People in Durango Today

Hispanic people have played a significant role in shaping the culture and economy of Durango, Colorado. Today, they remain essential to the community, contributing to its diversity, vibrancy, and growth.

In Durango, Hispanics comprise a significant portion of the population, comprising over 25% of the total residents. They have a strong presence in the local economy, working in various industries such as agriculture, tourism, and retail. Their contributions to the economy have been crucial to the success of many businesses and industries in the area.

The Hispanic community in Durango has a rich cultural heritage celebrated and honored throughout the year. The town hosts numerous events and festivals, including the annual Fiesta Days, which showcase Hispanic culture through music, dance, food, and art.

The Hispanic community has also played a vital role in shaping the local political landscape. Many Hispanic leaders have been elected to public office, advocating for the rights and interests of their community and contributing to the development of policies that benefit all residents.

In summary, Hispanic people in Durango, Colorado, are an essential part of the community, contributing to its economic, cultural, and political fabric. Their presence and contributions have enriched the town, making it a more diverse, dynamic, and inclusive place to live.